Ciao Amici, I send you and yours my good thoughts as we go through these days together…

Springtime Covid-19 Cleaning brought on some discoveries and inspired these thoughts…

In the springtime of uncertainty, there was certainly time to clean out closets. Strangely, burrowing in dark corners brought comfort. Outside were so many questions: When will it end? Will my loved ones suffer and die? Will I get it?

The answer was always: I don’t know.

But inside my closet were things I knew everything about. That Twiggy doll was a Christmas gift from Aunt Tuddy, there were faux pearl rosary beads I held tightly at my First Holy Communion. A button from a 1979 Patti Smith concert stirred up memories of a San Francisco summer—smell of eucalyptus, cool fog rolling in, pot of ratatouille on the stove of the crashpad. I even knew what happened after that summer: I married the guy I met at that crashpad, and now there he was, leaning into a Zoom work call at the kitchen table in Los Angeles…40 plus years later.

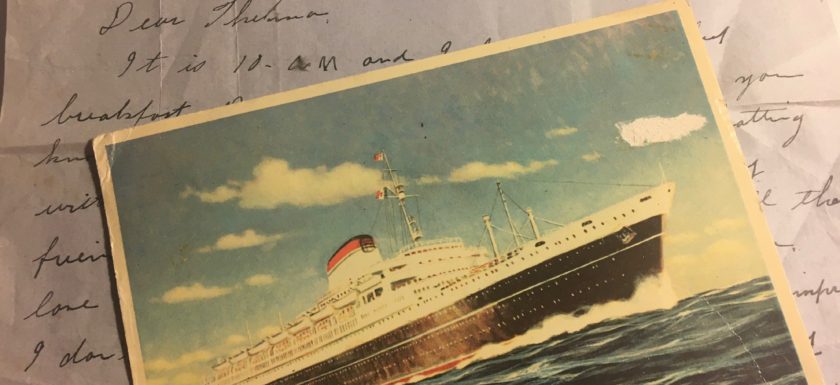

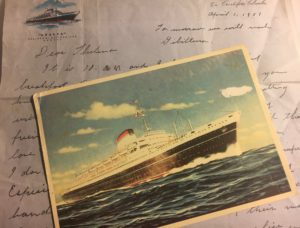

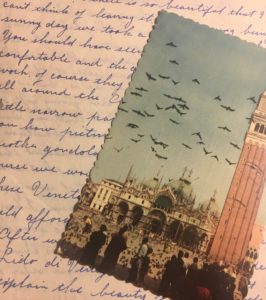

Back in the closet, at the bottom of a messy box, were a pile of letters my Nana had written to my mother, from a trip she took to Italy in 1957. When they first came into my hands a while ago, I’d skimmed them and gotten a little thrill, as they reminded me of a story Nana told me over and over when I was a kid. It began with her apologizing to me for not being around when I was born, telling me she’d been on a trip to Italy with my grandfather. Again and again I heard how a telegram arrived at their Venice hotel, and the story always ended with a cheek pinch and the words: “I ran out to the Grand Canal and told all the gondoliers Baby Susanna was born!”

Whenever I visit Venice, I love to imagine Nana broadcasting my birth. Little did she know how much that baby Susanna would grow to love Italy—-that I’d travel there every year, gasping over its beauties and deliciousness up and down the boot, and write books about it. In fact, I was supposed to be traveling there right now. Added to my many unknowns was the painful question: When will I be able to go back to Italy?

Gathering up Nana’s letters, I found the famous telegram, and took note of the hotel, a 3-star in the Rialto sestiere. A thought came that next time I’m in Venice, (hopefully very soon), I’d go there and do a re-enactment. Then, as always happens when I imagine Nana’s story, I got stuck on a part that never rang true for me. The part where Nana told me she ran.

As long as I knew Nana, her movement style was more of a slow waddle, from stove to kitchen table to rocking chair to bed. The Nana I remember was a soft, round woman who wore aprons tied under her baggy arms to shield her large shelf of bosom. She never drove a car, dyed her hair, or wore pants. At her most magical, she was in the kitchen with her wooden spoon or handing me a dollar bill from her worn out black leather handbag. Her colors were dusty rose and sage, her smells ragu and Coty powder. She surrounded herself with holiness: a gold medallion of the Good Pope, John XXIII, dangled from a chain between her breasts, there were Madonnas everywhere, and on her nightstand a miniature statue of Saint Anthony of Padua, Patron of Lost Things.

I cuddled up on the couch with Nana’s letters, arranged them in chronological order, and slipped into a Nana rhythm, slowly reading and sighing over onion skin paper and penmanship that would have made her nun teachers proud.

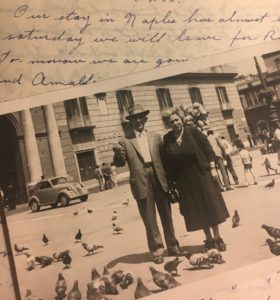

Afternoon hours drifted by as I followed a long leisurely trip that began with a transatlantic crossing on the Cristoforo Colombo, where Nana raved about all the activities—-mass, dances, and how Papa loved flirting with the pretty young blondes. They landed in an Italy I’ve only seen in movies: a chaotic scene at the Naples port with facchinos vying for tips, arguing over passengers’ steamer trunks. In my Papa’s hometown of Potenza, Nana wrote of a grand reception put on by elderly signoras all dressed in black. Along the Grand Canal in Venice she described boys in wool shorts hawking “So-DAH” to tourists. She adored Rome’s La Dolce Vita ambience, swooning over the elegant scene at Doney’s on the Via Veneto, where they stopped to join the fancy Americans for vermouth one evening.

I hunted through the pages for something juicy about what going back to the country where she was born meant to Nana. She’d left the village of Vinchiaturo in Molise with her whole family when she was three years old. My grandfather, who we called Papa, had come to America on his own from Potenza when he was 18. He landed in New York’s Little Italy, got work as a carpenter’s assistant in a piano shop, and with his earnings, one by one, sent for his sisters and parents to join him.

Fifty-plus years later, by the time this trip came around, Nana and Papa had achieved the American Dream. They lived in a big Victorian house in Newark, New Jersey, had raised four children and put them through college. Papa had worked as an insurance salesman, and upon retirement, celebrated by finally returning to Italy.

Reading and searching, I couldn’t find any mushy nostalgia from Nana for her homeland. She brought me not only to a different Italy, but to a different Nana. These were letters written by a lively 56-year old woman, who stayed up late enjoying nights at the opera—from Naples’ San Carlo to Milan’s La Scala, walked for hours tirelessly discovering new cities. She joked that she might forget how to cook, as she was always being waited on at ristorantes or with her Italian family and friends, who, in her words, “went to so much trouble”, welcoming her with lavish feasts.

It was clear from her letters that Nana thought she’d be going back to Italy, she even threw her coin in Rome’s Trevi Fountain to make sure. She had no idea that soon cancer would gradually turn her into a sad, semi-invalid. The magic Nana I knew as a kid would fade. She’d never return to Italy, where for that spring in 1957, she truly lived a dream.

Covered on the couch with her letters, I got restless, asking Why? Why had I only heard one story about this amazing trip again and again, when there were so many more stories Nana could have told me? The answer that came back was the same old I don’t know.

Memories rolled in, and with it the realization that I really never had any conversations with Nana. I was a top product of a generation when children were best seen and not heard. All that came back to me were the Venice birth announcement story, sounds of Nana cooing over my adorableness…(tesoro, come sei bella), or her murmuring about how she was going to make-a-the-ragu. And then there were the later years when I silently and impatiently stood bedside, listening to Nana complaining about how awful she felt.

Twilight came. I was stiff from the long couch sitting, and felt like Nana as I slowly peeled myself upright and waddled my way into the kitchen to pour a glass of red wine. I toasted New Nana, adding her to the big pile of things this big PAUSE gives us time to wonder about…

One thing became certain. Finally, after so many years, I had no doubts about Nana’s story. Finally, I believed her. I could see Nana, along the Grand Canal in Venice, on the day that I was born, with all the joy inside of her, running.

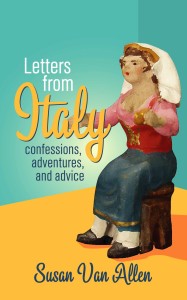

For More…, on Amazon, Kindle, or Audible…